The Chaotic 4th Quadrant: Where Models Fail & Startups Become Monopolies

We live a complex world where changes occur at breakneck speed. This is especially acute for those of us working in tech where 1) it’s difficult to foresee cause and effect and 2) even if you were right about the result, the impact of that outcome might be off. And in the world of rapid growth, big markets, and network effects, it’s arguably all about the magnitude of the payoff.

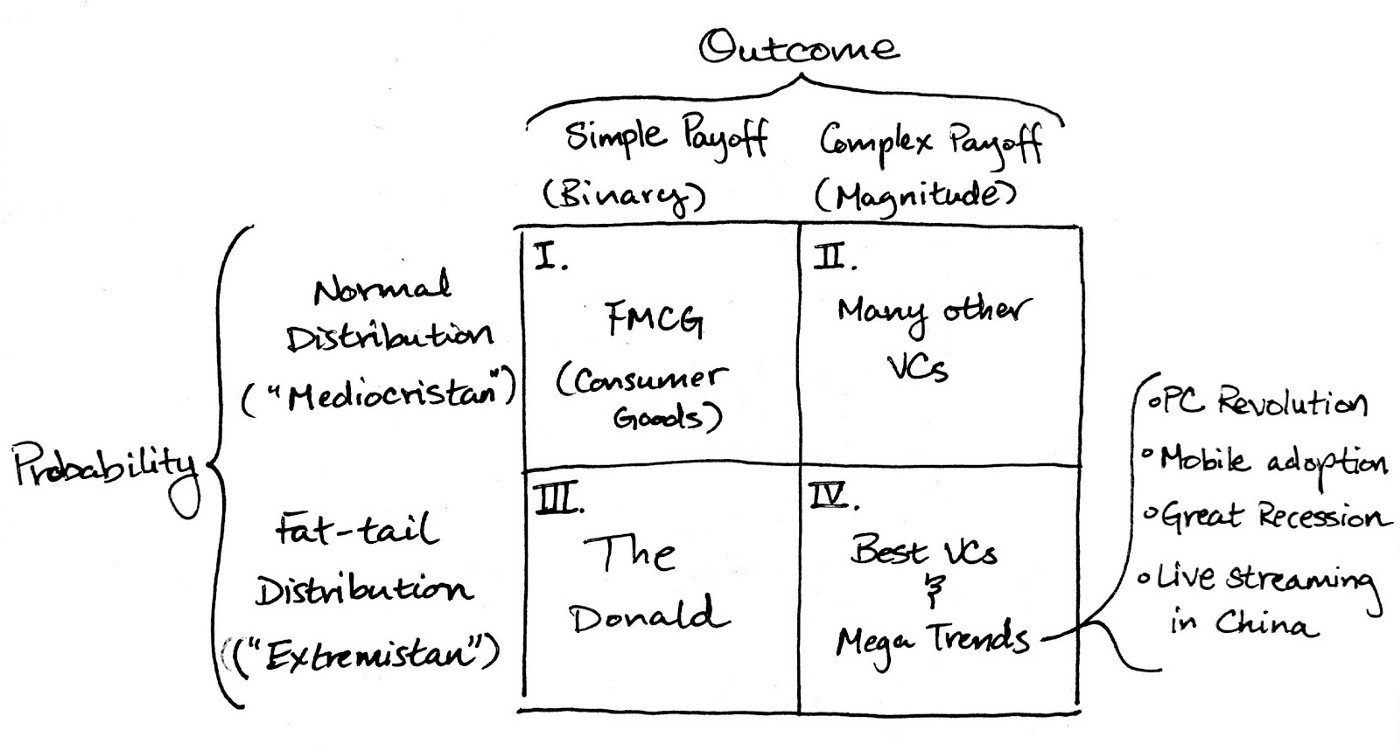

Nassim Nicholas Taleb author of Antifragile and The Black Swan, has a framework for gauging this more complicated model of probability and payoffs with magnitude. For the consultants reading, here’s a 2x2 matrix:

Outcome Columns

Simple payoffs (binary): being “right” is the only thing that matters: true & false, Trump vs Clinton (2016 election).

Complex payoffs (magnitude): “how right” is more important than just being right. For example, knowing that a war will occur is vastly different than understanding the magnitude of that war (WWII vs a border skirmish).

Probability Rows

Normal distribution (“Mediocristan”): imagine a normal distribution or cluster of data points that make for good linear regression analysis and predictive models. In other words, historical data is useful to predict the future.

“Fat tail” distribution (“Extremistan”): think outlier data points or power law distributions where the gains/losses are heavily concentrated on one side.

Taleb argues that statistics is useful for QI to QIII but lose their power in Quad IV. And indeed you see data being used to great effect with corporate sales projections (QI) as well as VCs that do their homework (QII) or take a data-based approach to identifying opportunities. Even the Trump election (QIII) was predicted by some analysts’ models.

However, it is in Quadrant IV where you can find so-called “Black Swans”, important but highly unpredictable events. This applies to the biggest tech trends (as well as the recent Great Recession) and it’s where startups become monopolies and the Midas List VCs make their fortunes. And while these developments might be rationalised in hindsight, no one at the time with historical data could have predicted both their outcome and magnitude.

To be clear, it is completely fine and can be very profitable to be operating in any of the quadrants as long as you are:

Aware of which quadrant you’re really in. Don’t fool yourself into thinking being right frequently is good enough (QIII) if magnitude matters much more (QIV).

Have the right expectations. If you’re working in a relatively predictable market (QII), don’t expect extreme outcomes (QIV).

Have the right strategy to take on the challenges of your quadrant. Data-based approaches are going to be much more effective in “mediocristan” (QI/II) than in “extremistan” (QIII/IV).

But if you do want to catch Black Swans in the chaotic 4th Quadrant, what can you do? In startupland, it’s about finding affordable optionality.

Finding (Affordable) Optionality in the Fourth Quadrant

Optionality, in common sense terms, means the ability to deviate from the original plan, which is valuable in scenarios where uncertainty is high. Stock options are valued higher than normal shares and a flex fare ticket that allows you to cancel 30 min before the plane takes off is going to cost you a lot more than fixed fare ticket.

Optionality in startups is having the breathing room to figure out the best way to dominate a market (i.e. business model, product, moats) before either the money runs out or the competition crushes it. Practically this translates to (these will probably be familiar):

A big market: not only allows several players to thrive, but also gives the entrepreneur room to pivot if the original solution doesn’t fit, as it often is the case.

An experienced team with domain expertise: benefits from the randomness of Quadrant IV as they are better able to adapt to new information as they explore the market. Second time entrepreneurs are especially attractive not because they know what works, but they likely know what doesn’t work.

A clean cap table that’s not overfunded: future fundraising options are limited if too much equity is already given out.

Various exit options: Whether the goal is to IPO, stay private, or get acquired, this is the ability to get off the bus and cash out when you want to.

An extraordinary network: this applies to VCs especially. One of the key strengths of a great VC is its network of portfolio companies filled with smart and ambitious people who interact and benefit from randomness.

While optionality is a good thing, it’s just as important to not overpay for it. For startups, that means considering the monetary, time, and focus cost of pursuing another monetisation strategy or testing out a feature. For investors, it means getting in early enough at the right price and securing the option of buying more equity later.

The game in the 4th Quadrant is to maximise optionality while minimising its cost. Here the concept of optionality is analogous to insurance companies and float — it’s not enough to have some float, you have to acquire it affordably and at scale.

Affordable Optionality is Everywhere in Tech

Here are a few examples to leave you with:

Revolut (mobile challenger bank) rapidly building and testing features that might hook in and monetise users. As Balderton Capital’s Rob Moffat noted, their ability to reduce cycle time (i.e. time and focus cost) to increase optionality is a huge competitive advantage in Fintech.

Niantic Labs (AR games) built the world’s largest database of hyper-local points of interest with its first game Ingress on the back of millions of users. It now has the option of launching other games on this platform. They’re still sitting on Pokemon Go because they happened to strike a gold mine on their second try.

Improbable (gaming & simulation platform) finding a new source of revenue helping the UK government simulate crisis scenarios while building the future Matrix. The cost of pursuing this new monetisation scheme is likely very low compared to the high fixed cost of developing SpatialOS and doesn’t deviate from its core mission at the least.

500 Startups (accelerator/micro VC) playing the numbers game with startup investing, especially in emerging markets. Play an active role in growing a nascent startup ecosystem, be first in line to invest a small amount in a lot of very early stage companies, and leave the option open to follow-on invest in the most promising ones.

Google investing in Algorithmia (marketplace for ML algorithms) to monitor emerging AI use cases. This is minimal cost to Google, with low downside risk (worse thing that can happen is it loses the money invested) and huge potential reward.