John Keynes Predicted Two Day Work Weeks - What Happened?

I absolutely loved Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals by Oliver Burkeman. He put into words many of the things I’ve also observed and believe in. One story that stuck out was that the economist John Maynard Keynes in 1930 predicted his grandkids would work just 15 hours a week thanks to the rate of productivity growth and automation.

“I would predict that the standard of life in progressive countries one hundred years hence will be between four and eight times as high as it is to-day. There would be nothing surprising in this even in the light of our present knowledge. It would not be foolish to contemplate the possibility of a far greater progress still.”

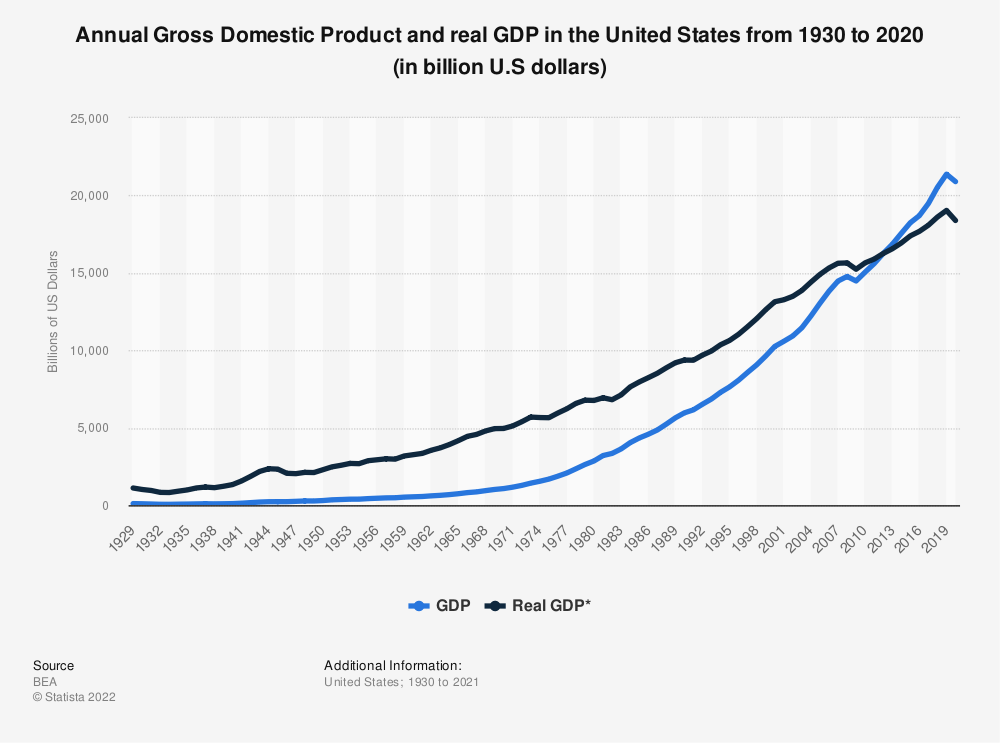

Based on his projections, by now we should all be enjoying 5-day weekends. We’ve in fact surpassed this. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) the average American worker productivity has increased 430% since 1950. Therefore, it should take either less than 10 hours per week to afford the same standard of living as someone in 1950 or our standard of living should be 4x higher.

Needless to say, this rosy future has not materialized. We’re still grinding away at 40-hour work weeks and our quality of life doesn’t feel any better than previous generations.

WE’RE CONSUMING MUCH MORE

Since the 1930’s our economy has grown a lot - we’re talking 20x in real GDP terms!

As our productivity increased, so did our incomes as expected. However, our consumption has also grown massively especially in the non-necessities or discretionary spending, which is anything not housing, taxes, debt and groceries. This includes cars, vacations, restaurants, entertainment, electronics. By the beginning of this century, our “leisure spending” had doubled to half of our total expenditures.

As our incomes increased, so did our consumption - especially on discretionary spending like cars, restaurants and entertainment.

This means we have to work more to sustain our increased leisure expenditures, which costs our leisure time. If you’ve ever taken on a pricey car loan, mortgage for a fancy house or, hell, bought a yacht, then your discretionary spending suddenly becomes your necessary spending in the form of debt and maintenance. Psychologically, the same thing happens when you buy a bunch of [enter your hobby of choice - mine’s outdoor and camping] gear and discover that you need to make more money to store them but no time to use them.

Also, income averages only tell half the story. It’s the distribution that matters.

SHARING THE REWARDS OF PRODUCTIVITY

First let’s differentiate between two common standard of living metrics: Income and Wealth. Income is how much a household makes on a regular basis while wealth, or net worth, is the household’s value of homes, business ownership, and financial assets like stocks, bonds, and retirement portfolios.

According to the Pew Research Center, the 1980’s marked the beginning of a steady rise in inequality as the income growth rates diverged between the poorest 20% and richest 20%, with the highest gains concentrated at the top 5% while squeezing the middle class. This means most people’s income growth doesn’t follow the massive upwards trajectory of our aggregate productivity GDP.

But income isn’t the only path to more leisure time because we need continue to work to generate that income. Wealth on the other hand can be used to generate passive income that “buy” time in the form of rent, recurring income, dividends, and large cash payouts.

We can also use wealth to guard against unexpected changes to income (volatility), access additional streams of capital like larger loans at more favorable terms, use that capital to gain additional streams of income (optionality). Since wealth is also tied to status, it can open more income opportunities (more optionality), hire money managers to smartly allocate resources and estate planners to protect intergenerational wealth. Wealth makes the rich more antifragile and likely to gain from chaos.

And boy have we gone through some chaotic times over the last two decades. The wealth of American families hasn’t changed since 20 years ago thanks to any gains being wiped out by the dot-com bust and the Great Recession. Yet the top 20% richest families were able to actually gain wealth since the last financial crisis.

The result is the wealth gap between the rich and poor more than doubled from from 1989 to 2016. We’re at a point where the richest 5% have more than 250x the wealth of the poorest 20%. This trend accelerated during the pandemic as the stock market rally favored those with capital. In mid-2021, for the first time ever, the top 1% held more wealth than the entire 60% American middle class combined.

Red circles are mine to emphasize the infliction points in which the rich have been able to bounce back from the three major economic shocks of dot-com, Great Recession and Covid. Meanwhile the rest of the population steadily declined in wealth.

I’ll save the drivers and societal repercussions of this trend for another time. For now, let’s just note that while our overall economic productivity has exploded, the ordinary person’s wealth has actually shrunk. More of us are working for incomes that drain our time to support high consumption lifestyles, while seeing our wealth, a key contributor to leisure time, being wiped out by economic turbulence.

But assuming we had the wealth and incomes to support more leisure time, will we know how to use it? After all, our quality of life has a lot to do with how we actually feel.

WE CAN’T STEP OFF THE GAS

The truth is we’re still part of a society where most people don’t know how to slow down even when we’ve gone past the point of sensible returns, happiness wise, for our work. Keynes acknowledges this too:

“Yet there is no country and no people, I think, who can look forward to the age of leisure and of abundance without a dread. For we have been trained too long to strive and not to enjoy. It is a fearful problem for the ordinary person, with no special talents, to occupy himself, especially if he no longer has roots in the soil or in custom or in the beloved conventions of a traditional society.”

Keep in mind this was written a century ago, which speaks to the enduring power of our hustle culture and human nature. It’s only reinforced when we’re around people who are also gunning ahead.

11pm in Dubai working on a product launch. I had many such nights.

When I was on the strategy team at Google, my colleagues were proud of the fact that they only took vacation when their paid time off (PTO) could no longer be carried over to the next month. In other words, they had to take time off. This only got worse as I stepped into Sturfee, a 14-person AI company, as the Head of Business Operations where taking my foot off the gas pedal felt like I was going to tank the company. Every week at the startup felt like it was a life and death scenario.

Therefore, it took enormous effort in late 2019 to peel myself away to Utah for a 2-week wilderness survival course. This was my first real vacation in years - that is if you’d count roughing it in the backcountry with little gear and losing 20 Ibs (15% of my body weight) from minimal food a “vacation”. Because I was going to be completely off-the-grid, I had to make sure all my bases were covered at work. This meant writing a 12-page documentation of all my roles and responsibilities, assigning my colleagues to cover each area in my absence, notifying all our partners, customers, and investors of these new points of contact.

It was a ton of work just trying to take time off work! No wonder I never felt like going on vacation - the hurdle was just too high to do it on the regular.

When I returned, however, everything was still intact. The company didn’t implode, our business deals weren’t jeopardized, no one dropped the ball. To my surprise, everything was humming along just fine without me. This floored me because in the two intense years I had been at the startup, I always thought that I was a critical part of its operations. And in many ways, I was, but if I took the right steps to set expectations and prepare the team for my absence, things would be okay.

Even more astounding was that I wasn’t that important anyways. I realized that I had tied my identity and sense of purpose to my job. The busy-ness of the business kept me running on a hamster wheel of self-perpetuating self-worth. It didn’t even matter who I worked for or what I worked on, for I was constantly on the move for as long as I could remember. From one company to another, changing roles and teams, hopping around continents, all the while thinking that I was the linchpin. Even more insidious was how this constant movement distracted me from focusing on my relationships and personal growth.

After 10 years of hustling in the tech industry, I had little community and purpose outside of the projects I led. I was afraid of stopping because it meant facing who I was and what I was lacking. Even if I were given three extra days off, I wouldn’t have known how to use it. Keynes seemed to know this intuitively as well.

“Thus for the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem - how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well.”

HOW TO USE OUR LEISURE TIME

The ancients had an answer to this dilemma. Aristotle saw leisure as the

“The goal of all human behavior, the end toward which all action is directed.”

To him, leisure was life’s top priority, in which our work should free us from the necessities of life to pursue.

But his definition of leisure wasn’t about relaxation (nevermind that our modern day version of leisure with all its planning and check box ticking is anything but relaxing) or amusement, but rather about becoming “a complete, well-rounded human being”. In other words, leisure is an internal, noble endeavor of developing our mind and character, of discovering and doing things that bring us lasting fulfillment.

What an idea. What if each of us could have three additional days to focus on ourselves? First of all, we wouldn’t need two weekend days just to recover, which is necessary self-care in our hustle society. We’d get three more days to journal, read, and learn new skills. To take on new challenges without the fear of ending up on the street. To spend actual unhurried quality time with our friends and family, to deepen our community ties, to educate ourselves about our politicians and the issues that matter, to learn of what happens beyond our borders, or even book a flight to those places we’ve bookmarked on Instagram. Imagine that.

This is a reality in which we’d know ourselves and the world because we have the time to dig deeper, within a society that supports and encourages this endeavor as “the end toward which all action is directed”. With this knowledge, we would feel more secure internally and externally. More reflective of our past to honor and appreciate our experiences and what we have. More sure of what we stand for and where we want to go. To find our personal path to purpose and fulfillment. To be allowed the space to appreciate our connectedness and cultivate the patience to overcome our differences.

Any creature can consume, but as humans, we are gifted with reasoning and awareness to discover and to create. This is our nature and what differentiates us from every other animal on this planet. Yet we are not allowed the time to use it within a system that wants us to do the opposite. In our current paradigm, none of us can actually be effective members of a healthy society because we can’t see beyond the 15-foot fog view of daily obligations nor escape the endless cycle of work and recovery. We can’t exercise our true gifts to benefit ourselves and others - or rather the benefits of our work is going to a select few.

There are external societal factors that need change. But so much is already within our control. Quality of life, unlike standard of living, is subjective and internal. In response to the question of what is the proper limit to wealth, the Stoic philosopher Seneca answered:

“It is first to have what is necessary and second to have what is enough.”

For those of us who are fortunate enough to have what’s necessary, it’s for our benefit that we differentiate between the two. Because if we don’t know what’s enough, we’ll always feel poor and miserable. If we don’t know that line in the sand, we’ll always be subject to the whims of others, to be told what we should want, what we should buy, how we should live. We will never be at home within ourselves nor find lasting happiness and contentment, while our planet buckles under the weight of our combined material discontentment. Our civilizations can bring us what’s necessary, but only we can say what is enough.

What’s Brewing (Newsletter excerpt)

🏥 Speaking of standards of living, this graph shows how much the US lags behind other rich countries when it comes to life expectancy compared to healthcare expenditure per capita (it’s pretty significant especially on cost). The line starts diverging around 1980 when the wealth gap also began widening. Interesting correlation.

🌆 I’m reading A bridge to meta-rationality vs. civilizational collapse, an amazing essay about how pure rationality will sink our civilization and that we need to develop to Stage 5 meta-rationality to prevent its collapse.

At the core is Robert Kegan’s three stages of adult human development framework: Stage 3 (pre-rational), Stage 4 (rational) and Stage 5 (meta-rational). Many STEM people like scientists and engineers are at stage 4 because of their formal rational training and disposition towards using logic for work and life. However it turns out reaching stage 5 is pretty hard and involves a lot of luck, pain and hard work - and also because our society, which runs on a stage 4 capitalistic platform mixed with stage 3 emotional/tribal elements, has little to no support to get folks to stage 5.

In other words, there’s currently no bridge between stage 4 rationality and stage 5 meta-rationality. The result is smart people who otherwise could make positive impact on the world get stuck in Stage 4.5, a state known as “nihilistic depression”. This piece spoke to me because it’s a problem that Silver & Steel (and Mind Map Nation to some extent) is trying to bridge.